In 2022, Yeshiva University Museum (YUM) received an Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) grant to collaborate with the Center for Jewish History to digitize 61 wimpels in the museum’s collection, edit entries in the museum database (emu), enhance the metadata in the center’s digital asset management program (rosetta), and make the images available to the public in the Center’s online database. [click here to view the wimpels on line]. The project goal was threefold: a pilot to digitize and make all the museum’s holdings available online; to enable the general public, researchers and students to have safe, easy access to this treasure trove of material culture and historic and genealogical information; and to protect the wimpels which are fragile.

Yeshiva University Museum Blog

We have heard that book collectors start as readers. Had you been studying a particular work by Maimonides when you began collecting?

RH: Let me start by saying that I never dreamed about exhibiting. I am an Orthodox Jew, a man of logic and reason, and many of the things I had been reading were a stretch to me until someone handed me a copy of the Rambam’s Moreh Nevukhim (Guide of the Perplexed). This is a book that was made intentionally difficult to understand, so I started with a book written by Kenneth Seeskin, a professor at Northwestern. Then I had an “aha!” moment and decided I would try to tackle the real thing on my own. I would say that I am an amateur, not an academic, but there are many things written about it in English that gave me an opportunity to think about it on my own. Once it clicked in my head, it helped me synthesize faith and reason.

So how did the collecting start – what was the very first book you acquired?

RH: One of my good friends who is a collector of Judaica said to me, “I know you have an interest in the Rambam. Have you ever thought about owning a rare Rambam book?” He introduced me to a well-known dealer who showed me an Italian copy of Moreh Nevukhim from the 1450’s or 1460’s. It was in perfect shape and had one beautiful illumination. It also came with a high price. So I was put in touch with Menahem Schmelzer, z”l, the chief librarian of JTS’s Judaica Collection, a wonderful person who spent time with me, a novice. I remember going to his office at JTS and he gave me a tour of the library and I just fell in love with these books because I was looking at living Jewish history. Dr. Schmelzer helped me authenticate the Italian Moreh Nevukhim and I was ignited with a passion. My friend warned me that I needed to be careful – this could become a serious addiction to books. But I said I was only interested in Rambam.

You have quite a number of Yemenite manuscripts. Is there a story behind that?

RH: Rambam had a remarkable relationship with the people of Yemen. They revered him. The Kapach family that goes back many years in Yemen were known for having manuscripts that have some different wording than manuscripts from other areas. Many people feel that the Yemenite manuscripts are the most authentic. Rav Kapach (Yosef Kafiḥ; 1917–2000) was a great Rambam scholar and had an extensive library, and after he passed, his wife, who was a tremendous baalat chessed (someone who epitomizes loving kindness), started selling some of the manuscripts. This first one I acquired, Sefer haMitzvos, was from 1492. Yemenite letters are bigger, bolder, and they use a red ink for some of the words that stayed vivid for 500 years in the hot, dry, climate. A chareidi scholar came to see the Sefer haMitzvos one day and was astounded to see some words that were different, and now understood it more clearly.

How did you and David Sclar (guest curator for the exhibition) meet, and when did you realize this would make a great exhibition?

RH: I met David a long time ago when he was an assistant at JTS library, a genuine researcher. He puts his heart and soul into it. He knew Dr. Schmelzer and was familiar with many of the booksellers. I decided that I should hire him every time I found something interesting in a particular book to do some more intense research. We became very close friends. Over the years, he said “Let’s catalogue this!” I didn’t realize, first, that I had amassed such a large grouping of Rambam books and second, that somebody might want to see it as an exhibition. I would exhibit them to my close friends and family. The very Orthodox would look at the books as “kedusha”, holy. My more secular friends would understand the historical value. And then you get those who ask, “So how much was it?” I think it was Sharon Mintz who started the conversation about exhibiting the collection.

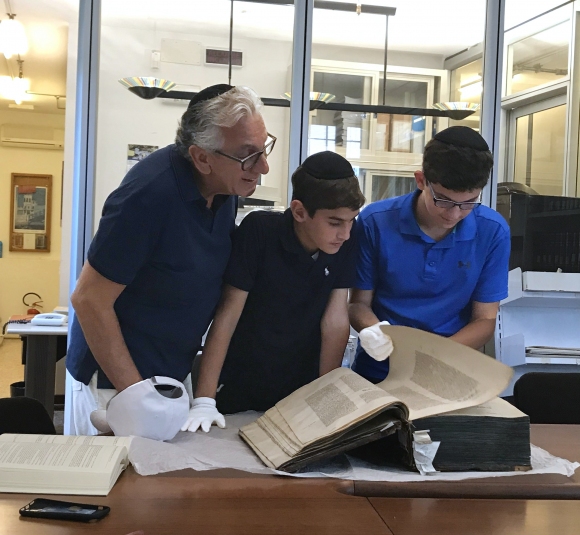

In your Collector's Preface to the exhibition catalogue, you mention the joys of exploring the collection with your children and grandchildren. How do you make Rambam relevant for young children?

RH: Many of my grandchildren live in Chicago and they come over a lot. You’d think that little kids would be bored by the Rambam books, but I am by nature someone who likes to tell stories. If you tell a story, that brings it to life for them. One of my grandsons is a Straus scholar who will be graduating from YU this year. He was my trusty assistant from a very young age because he was a strong kid – and books are heavy!

Robert Hartman with grandsons

The interview was conducted by Ilana Benson, YUM's Director of Museum Education, in April 2023.

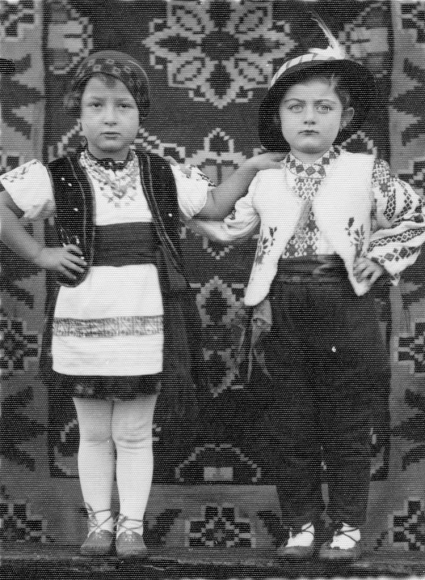

Looking through photographs of families, Purim plays, and couples dressed up in costume, there were two photos in the Yeshiva University Museum collection that I found to be the most striking. Both are from the early 20th Century, perhaps even from the same year or photographer. One, Tanschele in Purim Costume, is known to have been taken in 1936. The other, Rose Fischer and Friend in Purim Costumes, is dated early 20th Century and was presumably taken around the same time. In Tanschele in Purim Costume, the two children in the photograph are dressed in costume yet have very serious expressions. This contrast is striking, but not surprising in the context of other photos from Poland at that time which are stiffly posed with unyielding expressions. The second photo, Rose Fischer and Friend in Purim Costumes, has a similar feel to it, however, these children seem to be more in the spirit of the holiday. One child has a smirk on their face, a notably playful and unusual expression for a photo taken at the time. While this expression might be exceptional, it is distinctly within the spirit of Purim.

I found this set of photos so intriguing because they highlight how strong a tradition of dressing up there is on Purim. These photos strike me as being characteristic of the life that those in Europe were living right before the start of World War II. They are both a window into the lives that these children and their parents led before the war, as well as into the strong tradition of dressing in costume. The sheer number of photos of people in costume in this collection alone tells the story of the broader community's tradition.

It seems that no one is confident as to when this tradition actually began. It likely began in Medieval times, influenced by Mardi Gras celebrations, with the first reference to masks by a rabbi in the 15th century. Whatever the case, it is clear that this custom reflects the themes of the holiday – the theme of being hidden, just as G-d does not explicitly appear in the story, as well as the motif of disguising one's identity, as we are told Esther did. Most intriguing to me, however, was the story that these photos told at first glance.

When I think about Poland, my mind does not immediately go to pre-war life and what it actually looked like for those who were part of such a robust thousands-year-old culture. I am usually inclined to think about the Holocaust itself. However, connecting with photographs like these is an important reminder of where traditions come from and of how they were upheld by those living in Eastern Europe. As I thought about it, these photos and their associations represented two historical instances with eerie similarities. These children dressed up in silly Purim costumes right on the cusp of an evil being, like Haman, rising in power with the same intention. At both points in history Jews had to hide their identities, and some even felt as if G-d Himself was also in hiding during these years. Like Shushan, Jews were not able to be themselves and their destiny decreed by an evil force who was able to affect them in such a way perhaps because they were in exile. Having a flourishing culture stepped on and having to hide one’s own identity to be protected is a theme that echoes through both stories.

Something about these photographs is tragic. These children do not know that the story and triumph they are celebrating with these costumes is about to be repeated, perhaps on an even greater scale. Simultaneously, they represent the epitome of what we celebrate on this holiday. They are the hope of our nation, and after the Holocaust, are the revenge that we take on the Hamans and Hitlers of history. These children are depicted doing exactly that - continuing to preserve traditions that are about the victory and miracle of our existence. These specific children, such as Rose Fischer, are staring in the face of tragedy and another exile, yet they give us hope.

Tanschele in Purim Costume, Poland, 1936

Rose Fischer and Friend in Purim Costumes, Poland, early 20th C.

Poland, 1936

This poster honoring Pauline Dolinsky is dated December 26, 1918, just over two decades after the founding of the Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary (RIETS). Its highly stylized text contains a resolution passed jointly by the Women's Branch of Yeshivat Rabbi Yizchak Elchonan [sic] and the Ladies' Kohl [sic] Aid Society to honor the hard work of their shared president, Pauline Dolinsky.

This summer, I worked as a student assistant for Yeshiva University Museum. The Museum and its staff are important contributors to the study and preservation of Jewish history. I had the opportunity to acquire insights into both the development of museum exhibitions and the professional world of those people devoted to the study of Jewish artifacts.

With travel starting up again after pandemic restrictions, I would like to take you on a virtual trip to Israel, illustrated with objects from our collection. The trip will take a century. We will travel by multiple types of conveyance (train, ship, and plane), and bring back a variety of souvenirs.

Scarf Artist: Clara Gardon New York City, 1953 Silk, hand painted Collection of Yeshiva University Museum. Gift of the Artist.

Since most summer camps are currently closed, I thought it might be refreshing to share some of the artifacts in our collection relating to summer experiences of the past.

Laurence Goodstein and friends, Camp Oneida, Pennsylvania ca. 1915 gift of Dr. and Mrs. Laurence M. Lerner

One week after the holiday of Shavuot, we’ll mark the 53rd anniversary of a remarkable day – June 7, 1967 – when Israeli paratroopers entered the Old City of Jerusalem and reached Har Habayit, the Temple Mount, an area that had been off limits to Jewish people since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. Despite appeals by Israel to stay out of the Six-Day War, Jordanian forces had attacked Israeli cities, including sites in Jerusalem, leaving Israel no choice but to fight back. I remember that day vividly ...

Here in the U.S., my seventh-grade classmates and I were allowed to bring small radios to class so that we could listen to the news from Israel. We cried through morning prayers. We feared for the safety of Israel's leaders, of family and friends who lived there, and mostly of the brave soldiers. We never dreamed that our prayers would be answered by a seemingly miraculous reunification of Jerusalem. As we listened to the news reports, we looked at each other with an increasing sense of ecstatic but cautious disbelief.

In honor of Yom Ha'atzmaut, take a virtual tour of our exhibiition "From A to Z" with Tablet Magazine's Liel Leibovitz:

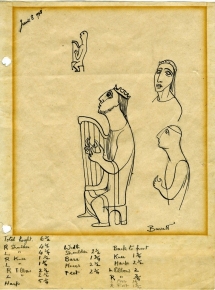

Oliver O’Connor Barrett, Homage to the State of Israel, study dated June 8, 1948. Collection of Yeshiva University Museum; Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Selig Burrows.

This is the seventh consecutive week we’re unable to welcome visitors in person at Yeshiva University Museum. It’s also marked by two extraordinary days, Yom Hazikaron (Israel’s Memorial Day) and Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israel’s Independence Day), which, linked back-to-back, help bring alive to Israelis that the very existence of the state was made possible by those who sacrificed their lives for it.

I am writing this on a Wednesday, and if this were a normal Wednesday, I would be at Yeshiva University Museum (YUM) in the Center for Jewish History, in our basement work room, sewing (by hand). I think back to the 1926 robe de style that I had begun conserving, the binder on exhibition that will need re-rolling, and the everyday maintenance we do for the costumes and textiles in the Museum's collection.

While we prepare for Passover 6 or more feet away from one another, we can longingly appreciate this David Dzienciarski painting of a Market before Passover from Yeshiva University Museum’s collection (gift of the artist’s estate). Created around 1970, the work depicts a crowded street in the Jewish section of Lodz, reimagined from the artist’s childhood. Pre-Passover activities are proceeding apace. Two men shoulder a cask of boiling water on a pole (the water would have been used to kasher dishes and utensils for the holiday); a rag seller offers up new plates in exchange for old clothes; shoppers go this way and that carrying their sacks and baskets; while children, oblivious to the surrounding chaos, roll hoops and play in between the harried adult bodies.

As richly evocative as the scene is, the painting is as far removed from documentary reality as we all currently are from our places of business and communal gathering. Dzienciarski (1912-1980), who miraculously survived World War II – first, as a member of the Polish army and then as a German prisoner – managed to escape eastward through the Russian frontier before making his way in 1948 to Israel, where he settled. This work was painted by the artist among tens of others while living in the new Jewish homeland decades after the leveling of the Lodz Ghetto and the decimation of European Jewry.

The son of a lumber and furniture merchant who traveled between Polish towns and villages by motorbike, Dzienciarski considered his paintings a mixture of observation and imagination:

“They are partially a documentary record and partially a personal vision depicting a way of life, which was suddenly erased and which tragically can never again exist. There is something in my paintings to which all can relate, but I believe they will have the greatest impact on the generations of young people who want to know what the Holocaust destroyed.” He viewed them as his life’s most important achievement, serving to make manifest for future generations a culture that no longer existed.

Market before Passover was exhibited among 35 works by the artist in a monographic show called “In My Mind’s Eye: Jewish Life in Lodz, 1920-1939,” presented by Yeshiva University Museum in 1980, around the time of the artist’s death. You get a sense of Dzienciarski’s creative relationship to observed reality from a photograph in YIVO’s collection showing Koshering Dishes for Passover in Lodz around 1920, when the artist lived there as a child (Courtesy of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York).

Perhaps we can take inspiration and derive strength from such a monumental and vital act of artistic preservation, re-creation and forward-looking-ness. Market Before Passover provides an imaginative window on another time and place, which is most welcome in the here and now, and could also helpfully remind us to avoid the crowds.

In the summer of 2019 I had the invaluable opportunity to do an internship at the Yeshiva University Museum in New York in fulfillment of requirements for my Masters degree in Fashion and Textile Studies: History, Theory, Museum Practice at FIT. Wanting to work with a collection dedicated to the preservation, study and exhibition of a broad spectrum of textile objects of the Jewish heritage, I came to the internship in order to see, touch, explore and contribute to the care of what I felt has yet to be given its fullest due attention in the narrative of world object history.

When we think of Rosh Hashanah

When we think of Rosh Hashanah, many of us think of the sound of the shofar, a literal blast from the remote past of Judaism, a time when musical instruments were in their infancy. It is a primal sound, heard through the centuries, calling the Jewish people.

It is with profound sadness that the staff, board and community of Yeshiva University Museum mourn the death of Dr. Vivian Mann, a teacher, scholar and friend, who brought enlightenment, creativity and deep respect for tradition to the study and appreciation of Jewish art and culture. While we are depleted by the loss of Vivian’s insightful eye, sharp mind and expansive vision of Jewish life and history, we will forever be strengthened and enriched by her research, exhibitions, students, and ideas. We extend our deepest sympathies to the members of Vivian’s devoted family. May they be strengthened by her remarkable legacy and comforted among the mourners of Zion and Jerusalem. May her memory be a blessing. Baruch Dayan Ha’emet.

These little figurines, approximately 5-7 inches high, are a hot topic in biblical archaeology.

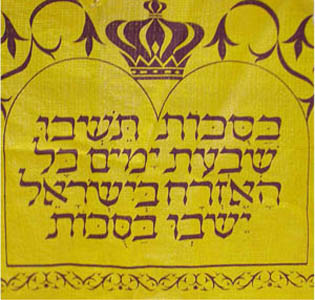

Sukkah decoration (details) by Siegmund Forst (1904-2006). Produced by the Spero Foundation. New York, ca. 1965. Collection of Yeshiva University Museum, Gift of Lynn Broide

In an attempt to gain as much experience as possible for a potential career in museology, I, Marc Fishkind, a rising Junior at the Frisch High School, had the privilege of embarking upon a five week “course” at the Yeshivah University Museum in an attempt to know what it’s really like to curate a museum. Under the guidance of Bonni-Dara Michaels I was given many tasks, from the mundane to the unexpected, that truly illustrated how much thought and work goes into every little detail within a museum. With the learning of a new computer program, hours of filing under my belt, and even practicing a mini lecture, I believe I have come out of this experience with a plethora of more knowledge and experience than when I began.

Wandering in our painting storage area this morning, I passed a painting by A. Raymond Katz depicting the production of matzah, and started thinking about the different ways artists have portrayed Passover. I thought you might enjoy it if I shared four examples from our collection that together illustrate Passover in a way you might not have considered before.

Reflections from YUM's Staff and Community

Reflections from YUM's Staff and Community