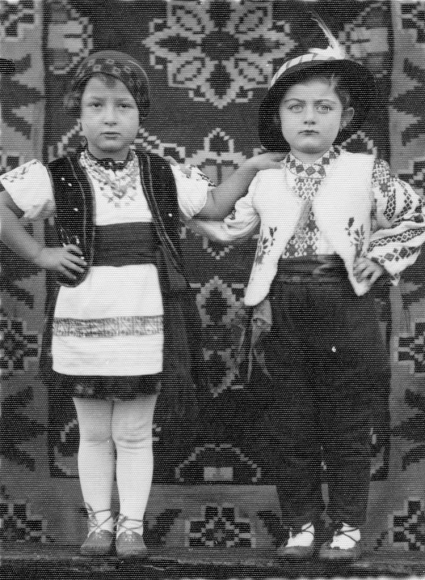

Looking through photographs of families, Purim plays, and couples dressed up in costume, there were two photos in the Yeshiva University Museum collection that I found to be the most striking. Both are from the early 20th Century, perhaps even from the same year or photographer. One, Tanschele in Purim Costume, is known to have been taken in 1936. The other, Rose Fischer and Friend in Purim Costumes, is dated early 20th Century and was presumably taken around the same time. In Tanschele in Purim Costume, the two children in the photograph are dressed in costume yet have very serious expressions. This contrast is striking, but not surprising in the context of other photos from Poland at that time which are stiffly posed with unyielding expressions. The second photo, Rose Fischer and Friend in Purim Costumes, has a similar feel to it, however, these children seem to be more in the spirit of the holiday. One child has a smirk on their face, a notably playful and unusual expression for a photo taken at the time. While this expression might be exceptional, it is distinctly within the spirit of Purim.

I found this set of photos so intriguing because they highlight how strong a tradition of dressing up there is on Purim. These photos strike me as being characteristic of the life that those in Europe were living right before the start of World War II. They are both a window into the lives that these children and their parents led before the war, as well as into the strong tradition of dressing in costume. The sheer number of photos of people in costume in this collection alone tells the story of the broader community's tradition.

It seems that no one is confident as to when this tradition actually began. It likely began in Medieval times, influenced by Mardi Gras celebrations, with the first reference to masks by a rabbi in the 15th century. Whatever the case, it is clear that this custom reflects the themes of the holiday – the theme of being hidden, just as G-d does not explicitly appear in the story, as well as the motif of disguising one's identity, as we are told Esther did. Most intriguing to me, however, was the story that these photos told at first glance.

When I think about Poland, my mind does not immediately go to pre-war life and what it actually looked like for those who were part of such a robust thousands-year-old culture. I am usually inclined to think about the Holocaust itself. However, connecting with photographs like these is an important reminder of where traditions come from and of how they were upheld by those living in Eastern Europe. As I thought about it, these photos and their associations represented two historical instances with eerie similarities. These children dressed up in silly Purim costumes right on the cusp of an evil being, like Haman, rising in power with the same intention. At both points in history Jews had to hide their identities, and some even felt as if G-d Himself was also in hiding during these years. Like Shushan, Jews were not able to be themselves and their destiny decreed by an evil force who was able to affect them in such a way perhaps because they were in exile. Having a flourishing culture stepped on and having to hide one’s own identity to be protected is a theme that echoes through both stories.

Something about these photographs is tragic. These children do not know that the story and triumph they are celebrating with these costumes is about to be repeated, perhaps on an even greater scale. Simultaneously, they represent the epitome of what we celebrate on this holiday. They are the hope of our nation, and after the Holocaust, are the revenge that we take on the Hamans and Hitlers of history. These children are depicted doing exactly that - continuing to preserve traditions that are about the victory and miracle of our existence. These specific children, such as Rose Fischer, are staring in the face of tragedy and another exile, yet they give us hope.

Tanschele in Purim Costume, Poland, 1936

Rose Fischer and Friend in Purim Costumes, Poland, early 20th C.

Poland, 1936